Music Without Borders: An Interview with Brendan Perry of Dead Can Dance

Photo Credit: Jay Brooks

Music Without Borders: An Interview with Brendan Perry of Dead Can Dance

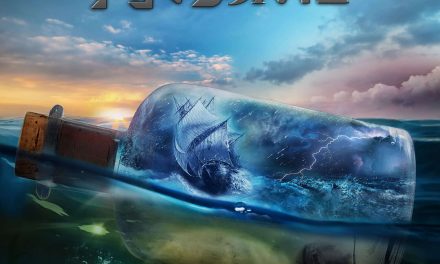

While working on his studio in France, I spoke with Brendan Perry of Dead Can Dance about their new album Dionysus. Dionysus is the Greek God of Wine and Dance, Fertility and Theater. In the two acts and seven parts, Perry and Lisa Gerrard create a story without words, a narrative using percussion, strings, synths and voices as well as many cultures’ instruments to draw the listener into a world of emotion and ecstasy, transporting our hearts and souls far away in time and place.

One of the many things I am interested in is all your instruments and where you keep them. At home or in the studio?

They’re in the studio, yeah. Of course, they have to be close to hand. When the inspiration comes you don’t want to be messing around, you want to seize the moment so I keep them close to me.

I imagine you having some friends over and having a drum and instrument circle and just jamming.

Those days are long gone. I have a handful of friends here. I had to kind of pretty much make new friends since I’ve been here. My daughter has gone to college, and it’s a real new beginning for us. I have a few musician friends but none of them play percussion. They’re all guitar-orientated.

You must have many instruments you learned to play, the kind you don’t just pick up and know what to do with.

It depends. My forte is fretted string instruments. I obviously started with guitar. Once you have that basic rhythmic coordination and finger to eye coordination then it’s not a huge, giant leap to learning more exotic fretted instruments. Like saz’s, baglamas and bazouki’s. The basic techniques are the same. It’s really the ear and becoming accustomed to tunings. In the case of oriental instruments the real kind of like learning curve is developing any of the quarter tone scales.

What is the instrument you feel the most adept at playing and what song we’ve heard it on?

Oh, hmm. The berimbau perhaps? It’s not very complicated, really, to get sounds from. The bowed instruments are from sample libraries anyway. The album and things we’ve done in the past are a combination of real acoustic instruments and also big libraries of instruments, sampled instruments.

When you started out was it all analog, instruments that you played by hand?

Yes. I suppose once I got into sequencing was when everything changed, really. Then, by MIDI you could have a synthesizer or sampler part of the musical tapestry. You can communicate ideas with keyboards, use them as a medium to write for samplers. Once you could sequence them then put them into loops, then it can open up a whole new world. The Ensoniq Mirage sampler was my entry point back in ’85, I think.

It sounds like technology aided you in being basically a one-man-band, right?

Yeah, absolutely. It’s been very liberating in that sense. It’s really just down to your imagination, your ideas. To take it to whatever level you want to. But having said that, there’s a craft to it as well. I go to great lengths to not just use the stock samples but actually go in and craft each sample meticulously so it expresses what I want it to.

With regard to the voices, the choral treatments on the album, half of them are sampled libraries that use these engines called Syllabuilders and basically, it’s a directory of syllables that you can put together. You can write sentences and phrases and then play them polyphonically. So you have these choral groups singing your sentences and phrases but in harmonies. It is very powerful now, what you can do.

That Syllabuilder reminds me of when I was a kid and we had a Commodore 64. I’m talking 64 kilobytes…

That’s what I had, that was my first sequencer.

My friend and I used the word processor, it was supposed to sound like a person talking, though we had to spell it out phonetically to actually make it sound human, and we used it to crank call his older brother.

I never used it for the sounds, purely as a sequencer.

Now here you are decades later using technology that allows you to create what we would hear as people singing words, or something like words.

Yeah, it’s a combination of that plus my and Lisa’s (Gerrard) vocals. In order to create a simile of a chorus, of people singing.

What is your favorite instrument? You said the fretted or plucked ones.

Guitars really. Electric guitars, acoustic guitars. I also really like the bouzouki and the saz. If it was a push comes to shove question, I’d say the electric guitar.

When I hear your music I don’t think electric guitars are involved at all.

Not on this album, no. To be honest, on each album we try to push the boat out and try something new. In this case we really pushed the boat out a lot further. But it was time to do that. There’s no point in going over old territory and it gets harder and more difficult to be original the further down the line you go. And it’s a challenge. I like a good challenge musically. It pushes you musically into areas that are unfamiliar territory and you’re exploring new ground and you’re learning about your capabilities and also your limitations. Yeah, it’s good to do that. Not enough artists do that. Unfortunately they all seem to stick to their old tried and true formulas that brought them success (Laughs).

I see you as the Indiana Jones of musical research.

(Laughs)

It’s obviously a universal one, because the spirit of Dionysus can be found universally. The essential agrarian form of Dionysus was probably the original cult, very much centered around the seasons, celebrating, planting, Spring and harvests. These kind of activities have been with humankind since the dawn of time and are still celebrated today.

At the very foundational heart level of Dionysus is a universal principle. So that’s why there’s Afro-Brazilian rhythms, Mexican-Aztec-Mayan instruments and musicality put in there too. To give it a more pluralistic view of the world, a more universal view of the world.

My word was exotic, but I like pluralistic. You’re not homogenizing the music at all, you’re saying it’s all connected. I enjoy that.

In a sense that’s what we’ve done from the beginning. Our backgrounds are, we’re the sons and daughters of immigrants. My family, in my lifetime went from London to New Zealand and I’ve been travelling since. It’s something in the blood now. So we reflected that, I think, in a more worldly outlook. We’ve been able to see what people have in common, rather than seeing their differences. Most people tend to be nationalistic, right-leaning and keen on pointing out people’s differences rather than what we have in common. I’m against that. Beyond border, beyond language we’re pretty much the same people everywhere. At least in my experience. Unfortunately politics and racism and all manner of negative things tend to try and say otherwise.

So you’re just trying to give everybody a big hug.

That’s it.

You worked again with Lisa, it wouldn’t be Dead Can Dance without her. How did you work together? In the studio in France?

I started the project, came up with the concepts over a year and a half ago. Just really started working, got everything arranged and developed it to a point where Lisa, when she was touring in Europe, she tours quite a lot in Europe now, in various projects, I get to see more of her now than I have done in the past. She dropped by for a month last year and we put down all her vocal parts when she was here.

This album was never going to be an album of songs. The voices have been sublimated into a choral group. Which is modeled on the ancient Greek chorus because there’s a direct connection with theater and Dionysus. Dionysus being the patron of the birth of western theater and Greek tragedy. It’s important that this was one of the things that was reflected in the work. So we took the concept of the Greek chorus, which is right at the beginning, the collective beginning of theater, and this becomes the narrative. There’s some choral responses with the individual singer but essentially, it’s really driven by the chorus, as a group. There was never going to be any individual songs or libretto, for that matter, because the subject of Dionysus isn’t really an intellectual one. It’s about energy and emotion. It’s like a sublimation of your dreams. To do something intellectual wouldn’t have been appropriate because of the subject of Dionysus. It’s much more rooted in nature, the mysteries of nature, the working of, the dynamics of the world. These cyclical, seasonal events that reoccur, like life and death, and what-have-you.

It makes sense that you wouldn’t include words because you want it to be accessible to all cultures.

And time as well. It had to sound archaic. The reason I chose a lot of the instruments was because they were old, they had an ancient pedigree. These instruments go back beyond written records. They’re really old. Obviously they’ve changed in their current form but their ancestors are really old. That was always going to be the foundational core for the album. To have something that links back to folk, rural, traditional music.

Did you listen to a lot of that traditional music?

I listened to a lot of music from Anatolia and from around the Black Sea, the Balkans, Sardinia, Corsica. I had a lot of that music already, in collections. The whole thing kicked off when I read The Birth of Tragedy by Friedrich Nietzsche. Then I read three more books on Dionysus. There was a lot of research that went in, right at the beginning, before I started work on it. The research goes on in terms of instruments. Just looking at anything in relation to Dionysus, documentaries, and looking at remnants of these ancient Dionysian festivals and where they still take place around the world. It was a long project.

Photo Credit: Stephanie Füssenich & Vaughan Stedman

I was wondering what you used in place of the traditional bass drum?

Well, there are bass drums, big, resonant bass drums but there’s also, I use a lot of sub-bass which is synths, but with very low frequencies. On one occasion I use contra-bassoons as well, really low woodwinds in combination with them, just to give a more moving air quality.

So we’re not hearing an electric bass guitar or a standard drum kit?

Absolutely not. There’s no drum kits, there’s no bass guitars.

I know your music means so much to your fans. Has there been any memorable things your fans have said to you about how Dead Can Dance has been included in their lives?

Everything from conceiving children to our music to giving birth to our music (laughs). Married to our music. It’s like we’re the soundtrack to people’s lives, it’s nice. People are pretty open about it. On the other side of the coin, people (play us during) last rights, they’re actually dying and want a connection with you. It’s beautiful in the sense that our music… our music doesn’t really have a literal meaning, it’s really all about emotion and atmosphere. Some people use it for meditation or rituals or whatever they get up to. I have no idea. It accommodates a lot of things because our music delves into many genres from singer-songwriter to full-blown, almost bordering on operatic, to poetry, so people apply our music to their own lives.

Your music is open to interpretation and it could be used for happy or sad occasions but I think it is more happy, I think your music means that much to people, so thank you. I was just listening to The Carnival Is Over and a few other songs and was getting chills because you’ve got such a great voice.

Thank you.

So, to wrap it up, I see that you’re touring in May and June of 2019 in Europe and hopefully you have plans to come to the States.

Yeah, it should be interesting, to see what happens after your mid-terms. Hopefully Trump will be impeached, and we can lift the Dead Can Dance embargo in America (laughs).

We have your music to listen to as the world burns.

I can grab my Nero fiddle. Seriously, we’re doing the European tour next summer and if all goes well in 2020 we’re going to extend that and then do a proper world tour. So we might make it out to the States in 2020.

But next year I’m also releasing a solo album and I’m touring Europe in February and March. Playing small, intimate clubs around France, Holland, Belgium, Germany and then after the Dead Can Dance tour I’m returning to do Eastern Europe with my solo shows. Basically, all next year is touring but the following year we’ll definitely be branching out.

Will your solo album be out before the tour?

No, probably in the Autumn, but I’m releasing some singles in the early part and kicking off the tour in February.

What/who will you be bringing out on the Dead Can Dance tour?

Eight musicians and my brother Robert is joining us. We’re doing a celebration of our musical legacy. We’re going to perform songs from studio albums that we’ve never actually played live before. Which we thought would be nice because we realized that the recent generations of listeners to our music never had the opportunity to see us perform live in the 80’s or even in the 90’s. So we thought it would be nice to revisit those periods of our earlier music and also to write new music to bring it up to date. It’s going to be fun.

We decided we couldn’t, it was too difficult to perform Dionysus for several reasons: it’s not long enough for a concert, so we would have to augment it with other material and we thought that would be too incongruous, these different musics; and it would take a lot of people to perform it. We’d need at least six singers, lots of multi-instrumentalists and it just became too impractical.

I think the audience will begin singing in tongues, and a drum circle will open up. I’ll get my wish. Your tours will be one long celebration and I look forward to seeing you in 2020.

Dionyus is out now.

(by Bret Miller)

Dead Can Dance Official Home Page

Dead Can Dance on Facebook